Fun Facts

(Fun) Facts about Thermodynamics, Heating Plant

Below are a collection of interesting facts and answers to questions about the central heating plant and thermodynamics in general.

>> CLICK on a question to reveal the answer <<

SNAPSHOT OF UW- STOUT’S DISTRICT ENERGY SYSTEM

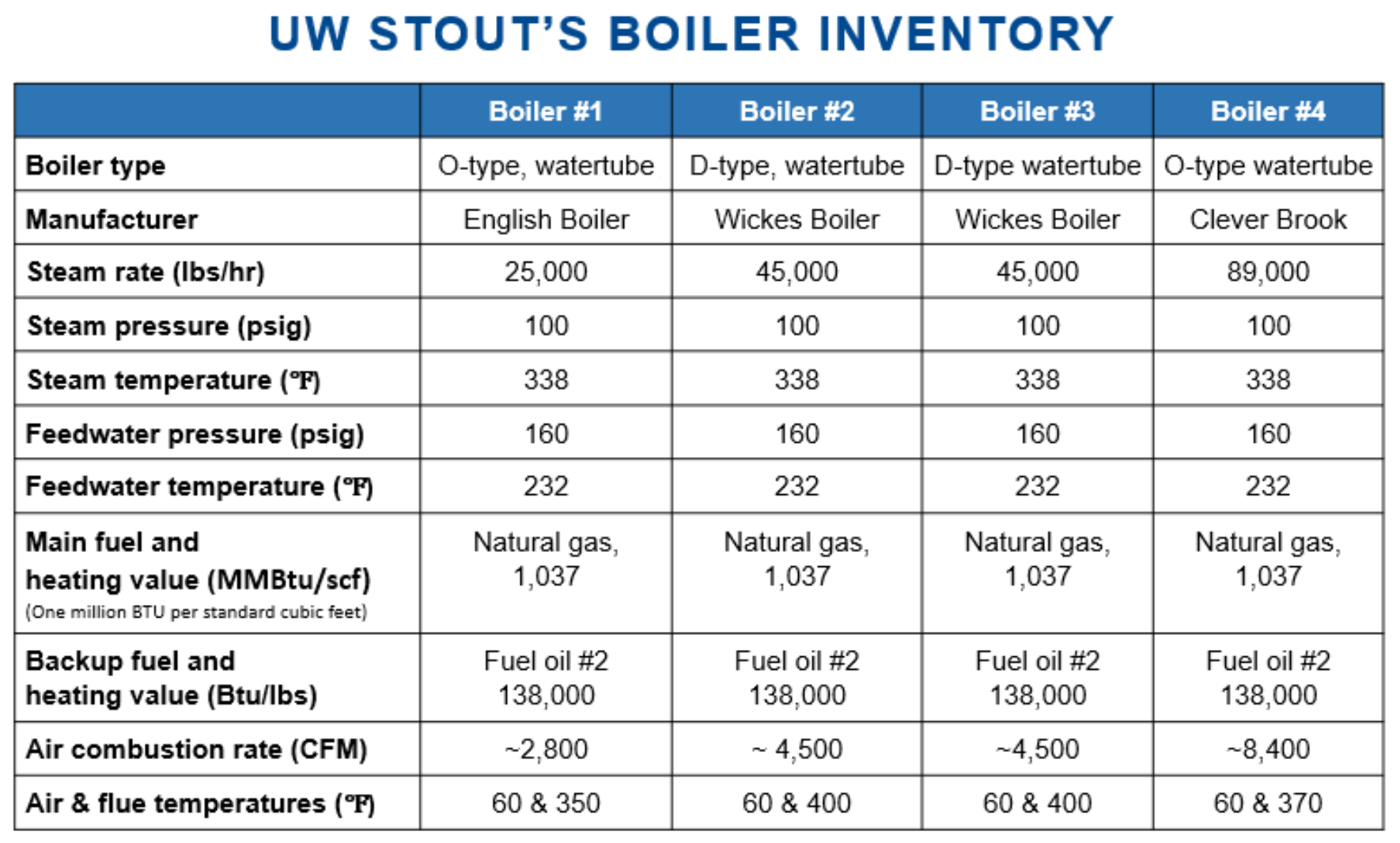

BOILER INVENTORY

WHAT IS THE TALLEST STRUCTURE IN MENOMONIE, WISCONSIN?

At 240 feet and 4-inch height, the red chimney of Stout’s heating plant is one of the tallest structures in Menomonie. The chimney was erected in 1965 by Consolidated Chimney Company, Chicago, Illinois using 89,800 red octagon and face bricks. A chimney is a structure for venting hot flue gas from the boiler to the outside atmosphere at a suitable height to ensure the pollutants are dispersed over a wider area to meet legislation and safety requirements. Its height is determined primarily by environmental protection agencies permitting ground-level concentration limits. It usually is cylindrical in construction and exposed to harsh environments inside and outside. With its abrasive and corrosive characteristics, flue gas can damage structural materials. For this, the chimney is built of brick.

HOW LONG IS THE UNDERGROUND HEATING AND COOLING PIPING SYSTEM AT UW STOUT?

Seven miles or about 37,000 feet.

The underground piping network system distributes steam and chilled water generated from the Plant to buildings around the campus to serve their heating and cooling needs. This network also includes the underground piping system that collects condensate and warmed water, after steam and chilled water have been used at the buildings.

WHAT IS THERMODYNAMICS?

Thermodynamics is the branch of physics that deals with the relationships between heat and other forms of energy. It describes how thermal energy is converted to and from other forms of energy and how thermal energy affects matter. The name thermodynamics itself is an example of a Greek technical term. Basically, it means the process of converting heat (thermo) into mechanical power (dynamics). Modern thermodynamics deals with more than just thermal energy.

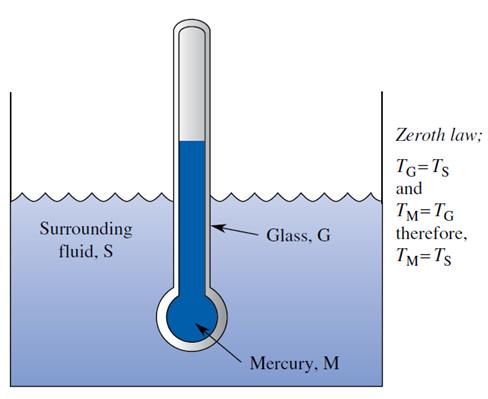

THE ZEROTH LAW OF THERMODYNAMICS

The zeroth law was one of the last thermodynamic laws to be developed. It was introduced by R. H. Fowler and E. A. Guggenheim in 1939.

One of the major values of the zeroth law is that it forms the theoretical basis for temperature measurement technology. Consider the mercury in glass thermometer shown in Figure. The zeroth law tells us that if the glass is at the same temperature as (i.e., is in thermal equilibrium with) the surrounding fluid, and if the mercury is at the same temperature as the glass, then the mercury is at the same temperature as the surrounding fluid. Thus, the thermometer can be graduated to show the mercury temperature, which is automatically equal to the temperature of its surroundings.

STATEMENTS OF THE SECOND LAW OF THERMODYNAMICS

There are three alternative statements of the second law of thermodynamics. They are the (1) Clausius, (2) Kelvin–Planck, and (3) entropy statements.

- The Clausius statement of the second law asserts that:

"It is impossible for any system to operate in such a way that the sole result would be an energy transfer by heat from a cooler to a hotter body."

- The Kelvin–Planck statement of the second law states that:

"It is impossible for any system to operate in a thermodynamic cycle and deliver a net amount of energy by work to its surroundings while receiving energy by heat transfer from a single thermal reservoir."

- The entropy statement of the second law states:

"It is impossible for any system to operate in a way that entropy is destroyed."

WHAT IS THE THIRD LAW OF THERMODYNAMICS?

Unlike the first two laws of thermodynamics, the third law is not a statement about conservation or production. It was developed from quantum statistical mechanics theories in 1906 by Walther Hermann Nernst (1864–1941), for which he won the 1920 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Basically, it states that the entropy of a perfect crystalline substance vanishes at absolute zero temperature and is independent of the pressure at that point. Therefore, if we choose absolute zero temperature and any convenient pressure as a reference state for an entropy scale, we have produced an absolute entropy scale (i.e., one with an absolute zero point). A pressure of 0.1 MPa (about 1 atm) is usually chosen for the reference state pressure. Consequently, we construct an absolute entropy scale from the point S = 0 at 0.1 MPa and 0 K.

HOW MANY LAWS OF THERMODYNAMICS ARE THERE?

There are four basic laws of thermodynamics: the zeroth, first, second, and third laws. Like all of the other basic laws of physics, each of these laws is a generalization of observed events in the real world, and their "discovery" was the result of an individual’s perception of how nature functions. Curiously, the order in which the thermodynamic laws are named does not correspond to the order of their discovery. The zeroth law is attributed to Fowler and Guggenheim in 1939; the first law to Joule, Mayer, and Colding in about 1845; the second law to Carnot in 1824; and the third law to Nerst in 1907. The first and second laws are the most pragmatic and consequently the most important to engineers. A thermodynamic analysis involves applying the laws of thermodynamics to a thermodynamic system. A thermodynamic system is a volume of space containing the item chosen for thermodynamic analysis.

WHAT IS HEAT?

In daily life, when talking about heat content of bodies or objects, we often refer to the sensible and latent forms of internal energy as heat.

In a technical sense, the word heat means thermal energy. Heat is usually defined as (thermal) energy transport to or from a system due to a temperature difference between the system and its surroundings.

WHAT ARE HEAT AND WORK ANYWAY?

Heat is usually defined as energy transport to or from a system due to a temperature difference between the system and its surroundings. This can occur by only three modes: conduction, convection, and radiation.

Work is more difficult to define. It is often defined as a force moving through a distance, but this is only one type of work. There are many other work modes as well. Since the only energy transport modes for moving energy across a system’s boundary are heat, mass flow, and work, the simplest definition of work is that it is any energy transport mode that is neither heat nor mass flow.

IS IT K OR ⁰K?

In 1967, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures dropped the prefix degree from the SI absolute temperature scale. So, we say “100 degrees celsius is equal to 373.15 kelvin” (or 100.00°C = 373.15 K). Notice that people do not capitalize the terms Celsius and Kelvin, even though they are proper names.

Also, in most textbooks and technical documents, people follow the same scheme of omitting the degree symbol on the Rankine absolute temperature scale, so 100.00°F = 559.67 R (and “559.67 R” is written out in lower case as “559.67 rankine”).

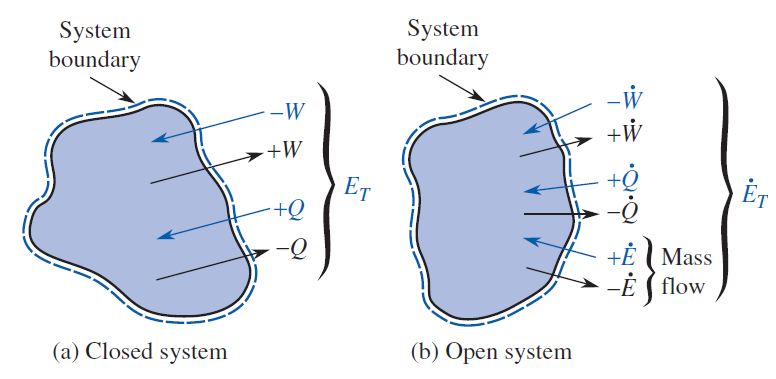

ENERGY TRANSPORT MECHANISMS

There are three energy transport mechanisms, any or all of which may be operating in any given system: (1) heat, (2) work, and (3) mass flow. These three mechanisms and their sign conventions are illustrated in Figure. Note that the sign conventions for heat and work shown in the Figure are not the same. Heat transfer into a system is taken as positive, whereas work must be produced by or come out of a system to be positive. This is the conventional mechanical engineering sign convention and reflects the traditional view that heat coming out of a system is “lost” (i.e., negative), while work produced by a system (such as an engine) should be assigned a positive value. By definition, a closed system has no mass crossing its system boundary, so it can experience only work and heat transport mechanisms.

WHAT IS A HEAT ENGINE?

A heat engine in Engineering Thermodynamics is a system that converts heat to mechanical energy, which can then be used to do mechanical work.

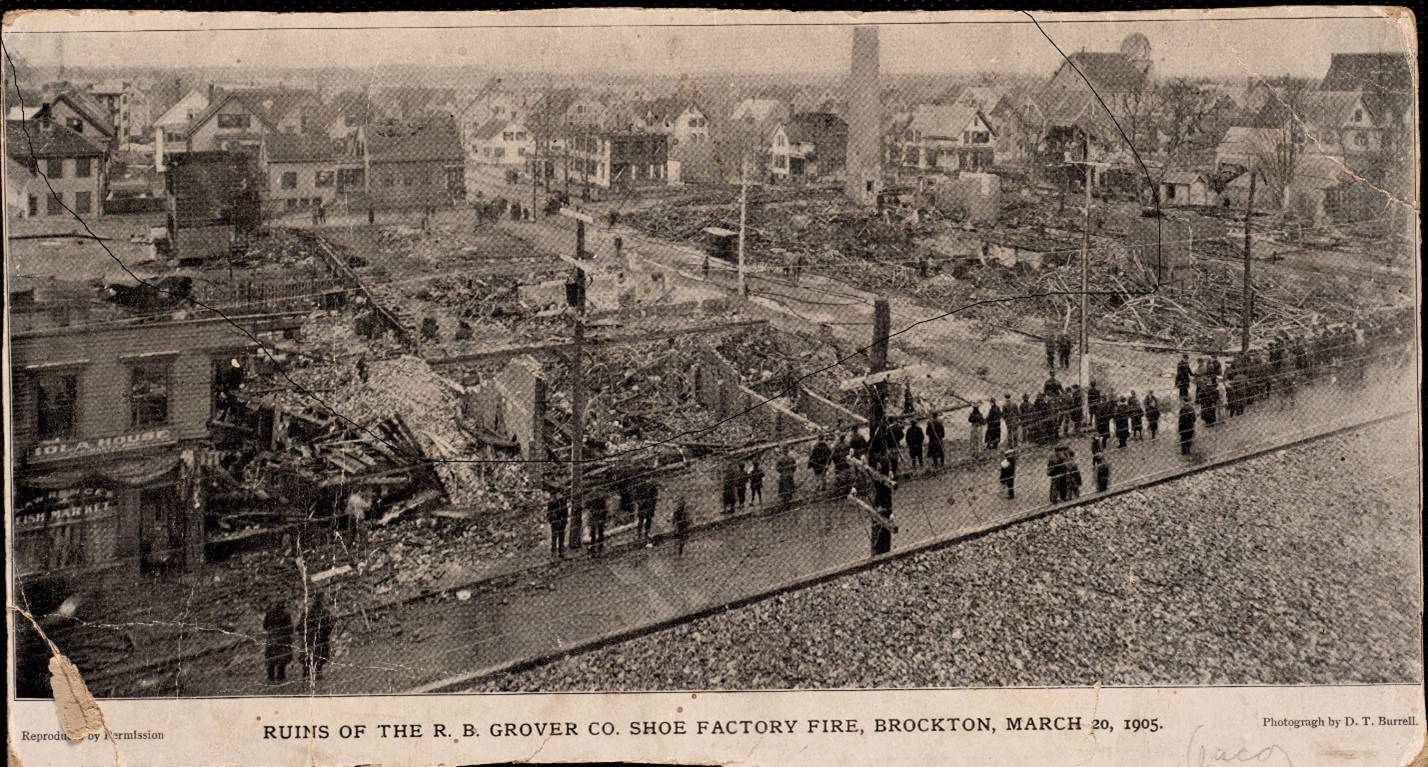

HOW DANGEROUS ARE BOILER EXPLOSIONS?

Between 1898 and 1902, there were 1600 boiler explosions in the United States, in which 1184 people were killed. On March 10, 1905, a boiler explosion in a shoe factory in Brockton, Massachusetts, killed 58 people and injured an additional 117 people. On December 6, 1906, a similar explosion occurred in a shoe factory in Lynn, Massachusetts. As a result of the ensuing public outcry, the state of Massachusetts enacted the first legal code of rules for the construction of steam boilers, in 1907.

From 1908 to 1910, Ohio and various other states enacted similar legislation, but because no two states had exactly the same code, boiler manufacturers had great difficulty satisfying all the varying and occasionally conflicting rules.

In 1911, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) joined with the boiler manufacturers to formulate a set of uniform standards for the design and construction of safe boilers. The first edition of the resulting ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code was produced in 1914, and by the 1930s, many advancements in boiler technology had been made. An updated and modernized version of this code is used throughout the industry today.

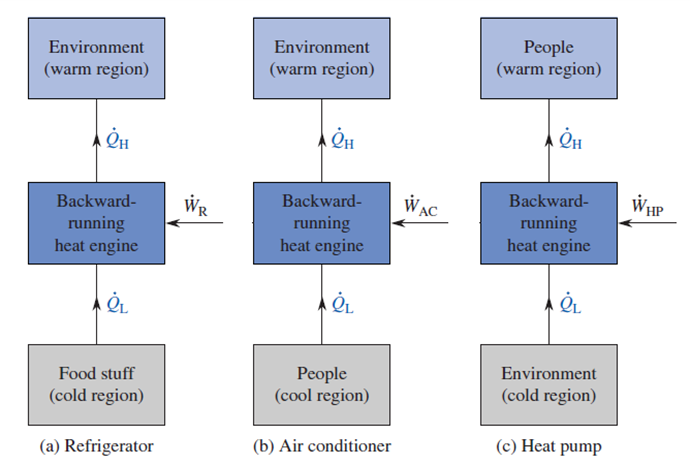

HOW CAN AN ENGINE RUN BACKWARD?

To get an engine to run backward, you need to put work into it where the work typically comes out. If the engine has an output shaft, you attach a motor or something to the shaft to turn it so that you are putting work into the engine instead of having it produce work. A heat engine converts some heat from a high-temperature source into work and rejects the remaining heat to a low-temperature sink. A “backward-running” heat engine draws heat from a low-temperature source, adds work energy to it, and rejects everything to a high-temperature sink.

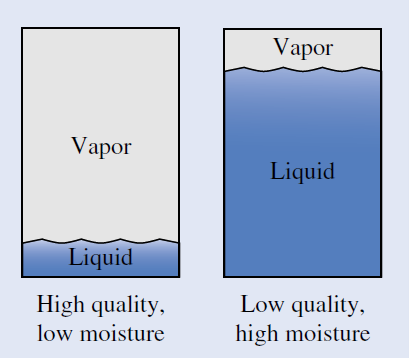

WHY DO THEY CALL IT QUALITY?

In the 19th century, there were a lot of steam engines. Railroads, factories, ships, and so on all used steam engines as their source of power. The people responsible for keeping these engines running noticed that they worked better if the steam contained more vapor than liquid. So, a mixture containing a lot of vapor and little liquid was said to be high quality. They defined this quality as the ratio of vapor's mass to total mass of liquid plus vapor. On the other hand, the amount of liquid present in a mixture is called the moisture of the mixture.

The condition where the quality x = 1.0 is reserved for saturated vapor and does not apply to superheated vapor. Similarly, the condition where quality x = 0 is reserved for saturated liquid and does not apply to compressed liquid. Note that the quality x of a liquid-vapor mixture can never be less than 0 or greater than 1.0.

WHY IS IT CALLED ENTHALPY?

The quantity u + pv has had many different names over the years. In the early years of thermodynamics, it was known at various times as the heat function, the heat content, and the total heat. The term enthalpy comes from the Greek meaning “in warmth,” and was introduced in 1922 by Professor Alfred W. Porter. He credited the coining of the name to the Dutch physicist Kamerlingh Onnes (1853–1926). This name was officially adopted by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) in 1936.

WHY USE F AND G SUBSCRIPTS?

The use of f and g as subscripts here is out of tradition. They come from the first letters of the German words flussig (for liquid) and gas. More appropriate English subscripts might be l for liquid and v for vapor, but they are not used.

WHAT IS A “TON” OF REFRIGERATION?

A ton of refrigeration or air conditioning is the amount of heat that must be removed from 1 ton (2000 lbm) of water in one day (24 hours) to freeze it at 32°F degrees Fahrenheit at 1 atmosphere pressure. It is also the amount of heat absorbed by the melting of 1 ton of ice in 24 hours at 32°F at atmospheric pressure. Using more conventional units, 1 ton of refrigeration equals 12000 Btu/hr.

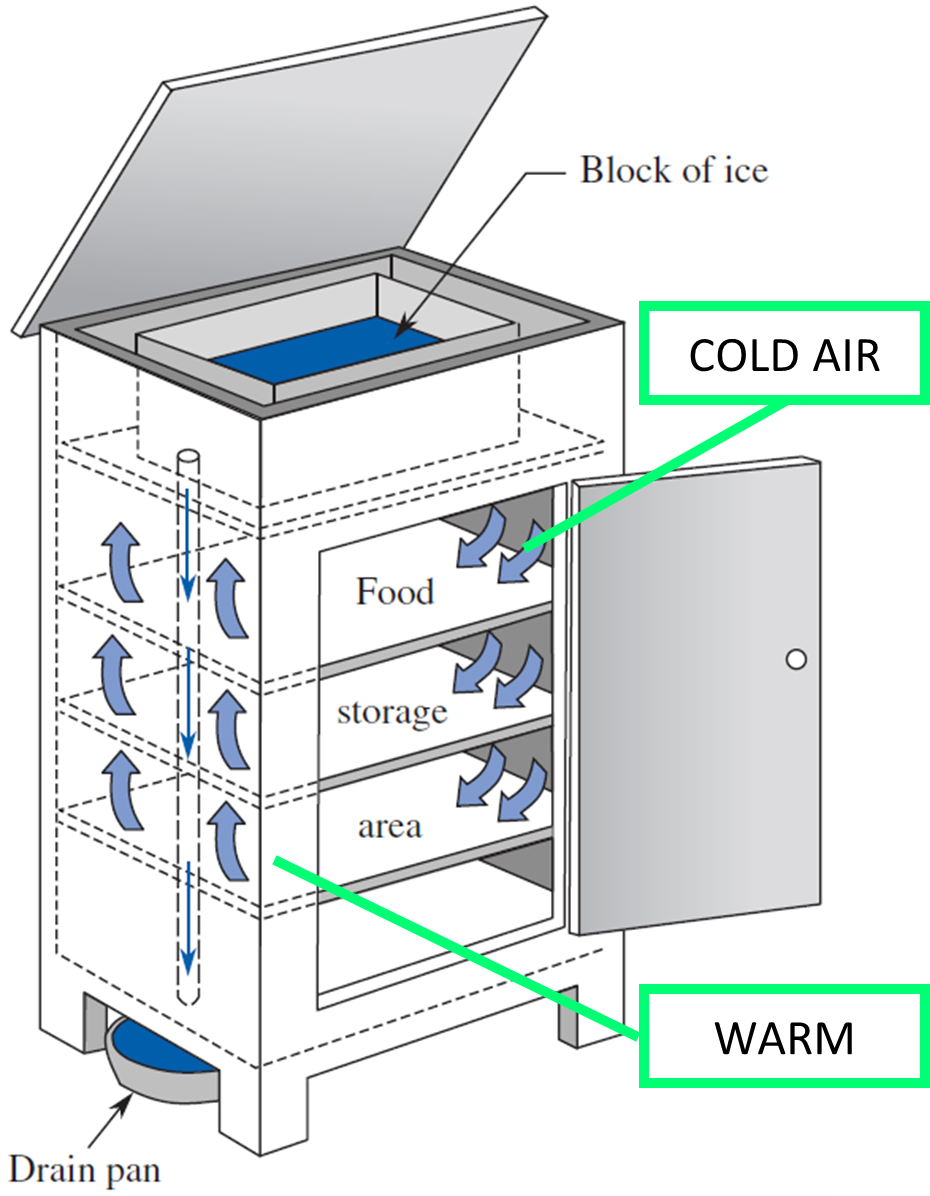

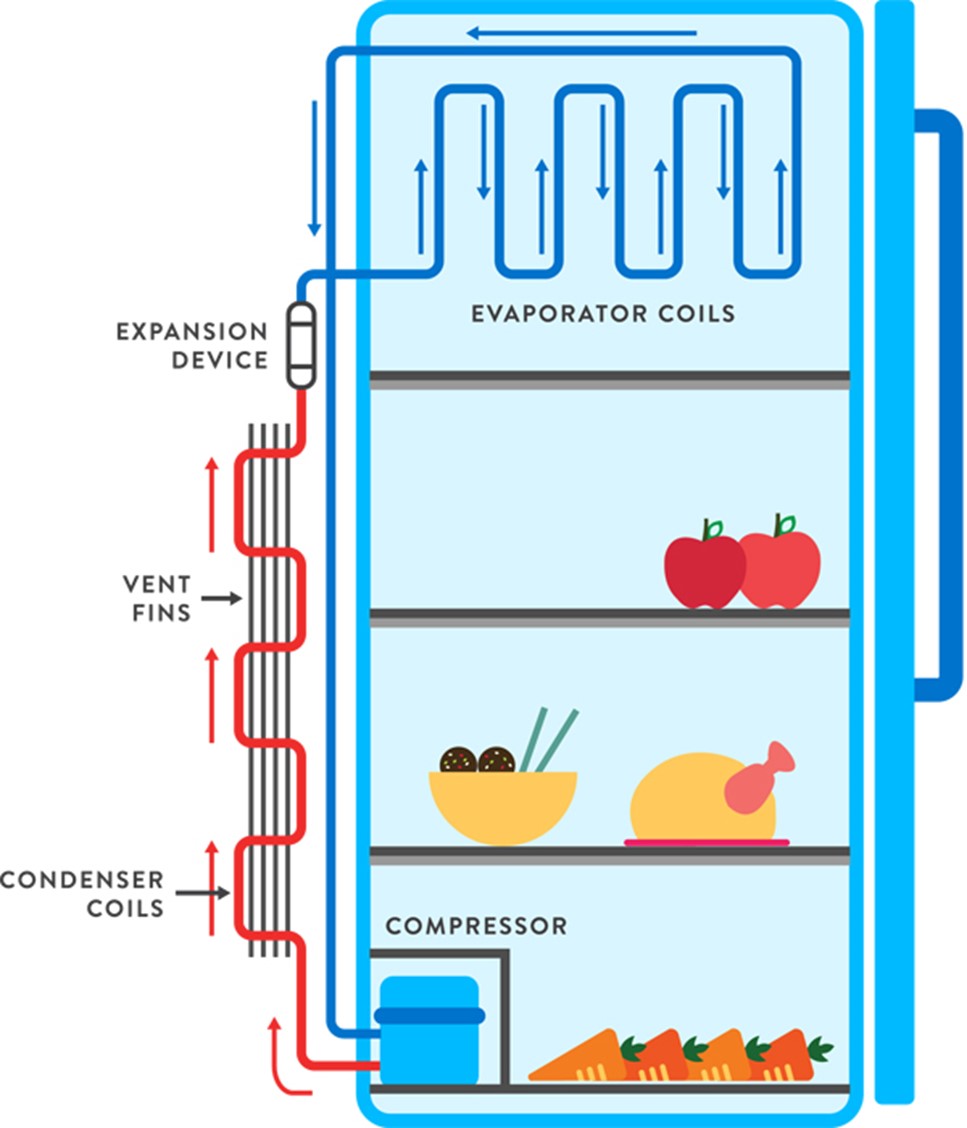

IS IT CALLED AN ICEBOX OR A REFRIGERATOR?

An icebox was a wooden box containing ice and food to be preserved. It is a compact non-mechanical refrigerator and was a common early-twentieth-century kitchen appliance before the development of safely powered refrigeration devices.

Originally, the ice was put on the bottom and the food on the top. But eventually, it was realized that this was inefficient because cold air is heavier than warm air. Thereafter, the ice was put on the top of the icebox, and the food was always placed below it so that the heavier cold air could circulate around the food. The icebox was invented in 1803 and manufactured in the United States until 1953. Ice needed to be added every day or two in the original iceboxes. But, by 1923, improved thermal insulation design required ice to be added only every five to seven days.

The term refrigerator is reserved for a device that does not use ice to produce cold temperatures, even though the device may be used to preserve food. There are vapor-compression refrigerators, gas expansion refrigerators, thermoelectric refrigerators, and so forth.

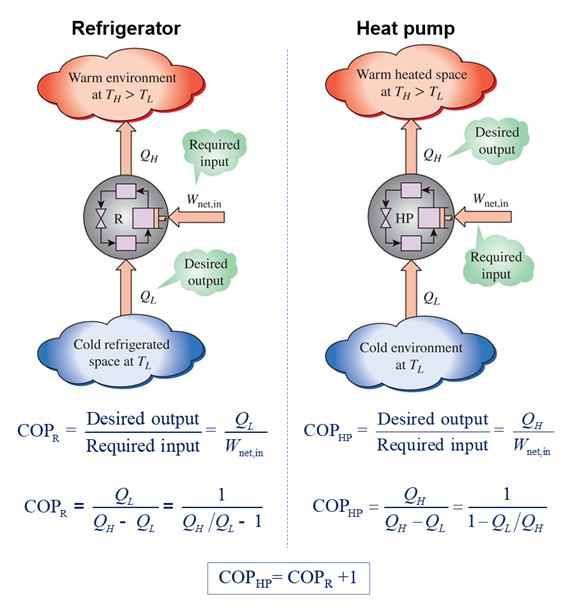

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A REFRIGERATOR & A HEAT PUMP?

The difference between a refrigerator and an air conditioner is one of purpose. The purpose of a refrigerator is to remove heat from a cold medium whereas the purpose of a heat pump is to supply heat to a warm medium.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A REFRIGERATOR & AN AIR CONDITIONER?

The difference between a refrigerator and an air conditioner is one of purpose. The purpose of a refrigerator is to remove heat from a refrigerated space whereas he purpose of an air conditioner is to remove heat from a living space.

IS THE EFFICIENCY OF HEAT PUMPS, AIR CONDITIONERS, AND REFRIGERATORS GREATER THAN 100%?

If you look closely at the thermal efficiency equations for heat pumps, air conditioners, and refrigerators, you see that their efficiency is going to be more than 100%, because under normal operating conditions, the numerator in their efficiency equation is usually greater than the denominator. Consequently, their energy conversion efficiency is usually greater than 100%.

How can that be? Nothing should have an energy conversion efficiency greater then 100%. But, it is correct. This is simply due to the way in which the thermal efficiency formula is structured:

Energy conversion efficiency = Desired energy output/Required energy input

This makes a heat pump much more attractive for domestic heating than, say, a purely resistive electrical heater. Electrical heaters convert all their input electrical energy directly into thermal energy and therefore have energy conversion efficiencies of 100%, whereas most heat pumps have energy conversion efficiencies far in excess of 100% for the same electrical energy input.

Since this could be a problem in public advertising, the industry uses the phrase coefficient of performance (COP) instead of efficiency. The COP is simply the pure efficiency number before it is converted into a percentage. For example, the COP of a heat pump with an energy conversion efficiency of 450% is 4.5.

WHAT ARE ENERGY SOURCES?

Primary energy sources take many forms, including nuclear energy, fossil energy (like oil, coal, and natural gas) and renewable sources like wind, solar, geothermal and hydropower.

These primary sources are converted to electricity, a secondary energy source, which flows through power lines and other transmission infrastructure to your home and business.

IS HYDROGEN A FUEL AND AN ENERGY SOURCE?

Yes, hydrogen is a fuel since it can be used in fuel cells to generate electricity or burned to create heat energy. However, hydrogen is an energy carrier, not an energy source and can deliver or store a tremendous amount of energy. Also, because hydrogen does not exist freely in nature and is only produced from other sources of energy, it is known as an energy carrier.

WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS OF CENTRAL HEATING AND CHILLER PLANT?

Central heating plant distributes thermal energy normally in the form of steam or hot water from a central source to residential, commercial, or industrial consumers for use in space heating, domestic hot water heating, process heating, cooking, and humidification. Thus, the heating effect comes from a distribution medium rather than being generated on site at each facility. Because the central plant is large, the campus can realize benefits of economies of scale.

- Recover and allocate mechanical electrical space for more usable use.

- Improved building aesthetics due to the cooling towers being eliminated from the roof top.

- Environmental advantages reduce carbon emissions and water use because fuels are burned to generate district heat within a central plant.

- Reduced maintenance and administration costs; staff can be reduced accordingly.

WHAT ARE Ccf, Mcf, Btu, AND Therms?

You can find these acronyms in many technical documents and natural gas bills.

- Btu — British thermal unit(s)

- Ccf — the volume of 100 cubic feet (cf)

- M — one thousand (1,000)

- MM — one million (1,000,000)

- Mcf — the volume of 1,000 cubic feet

- MMBtu — 1,000,000 British thermal units

- Therm — One therm equals 100,000 Btu, or 0.10 MMBtu

WHAT IS THE HEAT VALUE OF NATURAL GAS BTU?

The heat content of natural gas may vary by location and by type of natural gas consumer, and it may vary over time. The primary constituent of natural gas is methane, which has a heat content of 1,010 British thermal units per cubic foot (Btu/cf) at standard temperature and pressure. In 2020, the U.S. annual average heat content of natural gas delivered to consumers was about 1,037 Btu per cubic foot, or almost 2.7% more heat content than pure methane, reflecting the composition of the gases in the natural gas stream. Therefore, 100 cubic feet (Ccf) of natural gas equals 103,700 Btu, or 1.037 therms. One thousand cubic feet (Mcf) of natural gas equals 1.037 MMBtu, or 10.37 therms.

High-Btu natural gas contains higher concentrations of natural gas liquids (mostly ethane and some propane) that have higher heat content than methane. Pure ethane has a heat content of 1,770 Btu/cf and pure propane 2,516 Btu/cf. (Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration)

WHAT IS THE UNIT FOR NATURAL GAS PRICE?

In the United States, natural gas can be priced in units of dollars per therm, dollars per MMBtu, or dollars per cubic feet. The heat content of natural gas per physical unit (such as Btu per cubic foot) is needed to convert these prices from one price basis to another.

HOW DO I CONVERT NATURAL GAS PRICES IN $/Ccf TO $/Btu OR $/therm?

You can convert natural gas prices from one price basis to another with these formulas (assuming a heat content of natural gas of 1,037 Btu per cubic foot):

- $ per Ccf divided by 1.037 equals $ per therm

- $ per therm multiplied by 1.037 equals $ per Ccf

- $ per Mcf divided by 1.037 equals $ per MMBtu

- $ per Mcf divided by 10.37 equals $ per therm

- $ per MMBtu multiplied by 1.037 equals $ per Mcf

- $ per therm multiplied by 10.37 equals $ per Mcf

(Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration)

WHAT ARE PERPETUAL MOTION MACHINES?

Devices that supposedly operate using processes that violate either the first or second laws of thermodynamics or that are required to be reversible represent various forms of perpetual motion machines. When the operation of a device depends on the violation of the first law of thermodynamics it is called a perpetual motion machine of the first kind. For example, a heat engine that produces power but does not absorb heat from the environment.

When the operation of a device depends on the violation of the second law, it is called a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. For example, an adiabatic air compressor in which the air exits at a lower temperature than it entered.

No perpetual motion machines operate as proposed and have for centuries been the source of frauds brought on the unsuspecting public by unscrupulous or naive inventors.

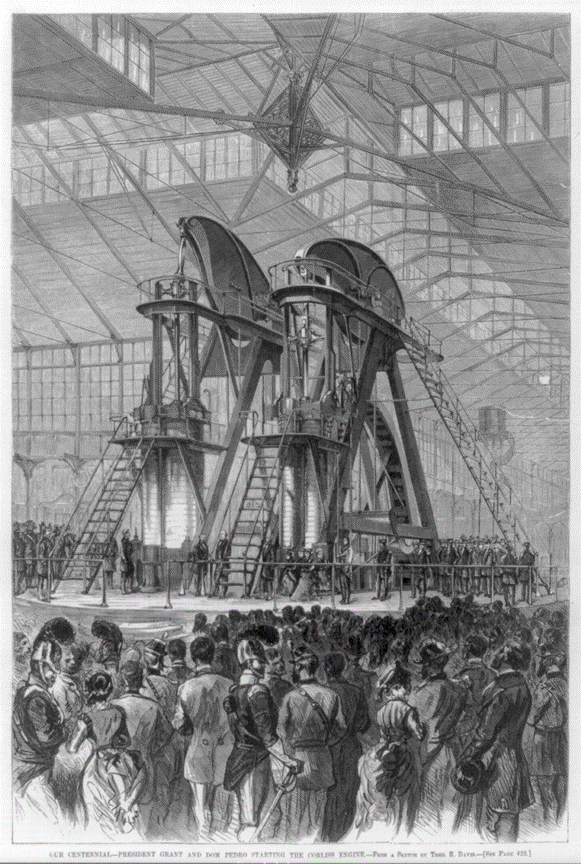

CORLISS STEAM ENGINE

In 1876, George H. Corliss (1817–1888) built what was then the largest steam engine ever made (Figure below), for the United States Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It had two cylinders, each with a 40.0-inch bore and a 10.0 ft stroke. Steam entered the engine as a saturated vapor at 100. psia, producing 1,400 hp at only 36.0 rpm. The engine’s flywheel was 30.0 ft in diameter and weighed 56.0 tons.

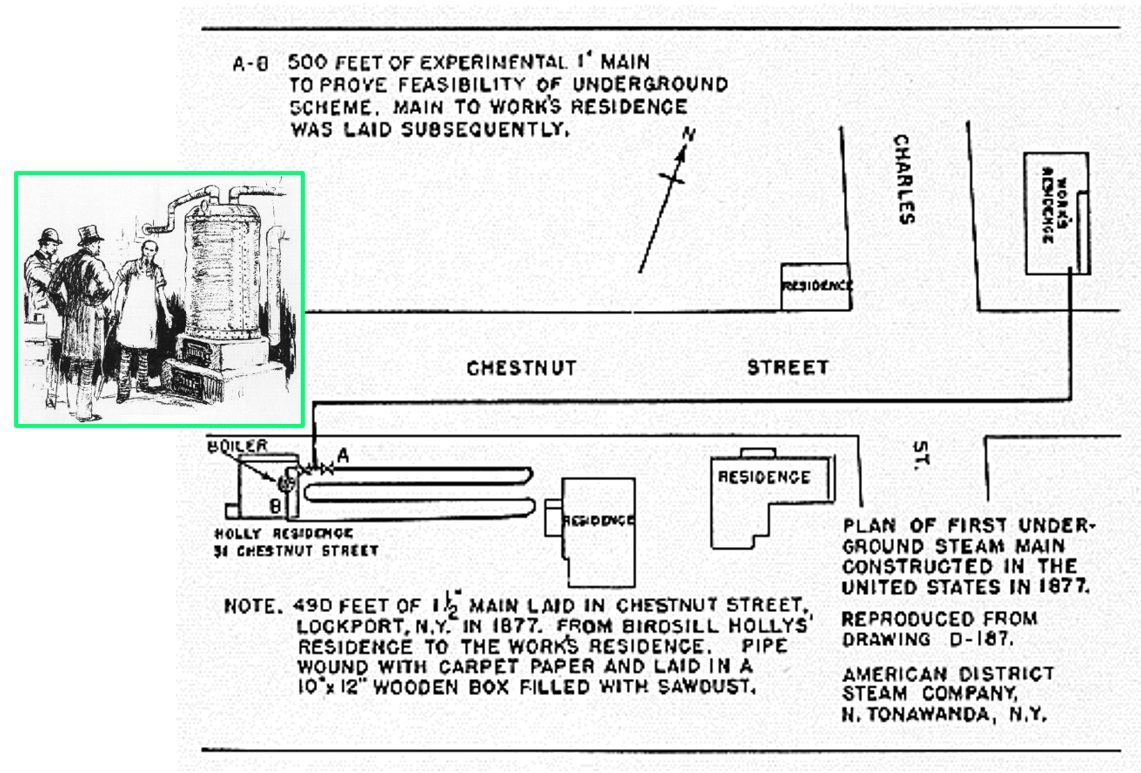

WHO IS CONSIDERED THE FOUNDER OF DISTRICT ENERGY SYSTEM?

District energy system is characterized by a central source producing hot water, steam, and/or chilled water, which then flows through a network of insulated pipes to provide hot water, space heating, and/or air conditioning for nearby buildings. The delivery of thermal energy from a central source is not a new idea.

- During Roman times, warm water was circulated through open trenches to provide heating for bathhouses in Pompeii. In the ruins are the remains of the old heating plants, for example, the one used in conjunction with the so-called Thermer (bath).

- In early 14th Century, people in Chaudes Aigues, France distributed hot water from nearby hot springs to provide heat source to individual houses through wooden pipes.

- In 1748, Benjamin Franklin built a fireproof flue system beneath the floor of several adjacent residences in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, so that they could be provided with heat from a central furnace.

- In 1853, according to the International District Energy Association (IDEA), the first district steam heating system in North America was installed at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

- In 1876, Birdsill Holly designed the Lockport system that provided steam from a central boiler plant to a few nearby residences and other users in Lockport, New York (near Buffalo). He is considered the first to put district heating on a successful commercial basis.

WHO INVENTED THE “OTTO” CYCLE?

Unknown to Nikolaus Otto (1832-1891), the four-stroke cycle internal combustion engine had already been patented in the 1860s by the French engineer Alphonse Eugene Beau de Rochas (1815–1893). However, Rochas did not actually build and test the engine he patented. Since Otto was the first to actually construct and operate the engine, the cycle is named after him rather than Rochas.

Right: Alphonse Eugene Beau de Rochas (1815–1893)